The Kremlin's repressive decade

Ten years ago, I had the honour of speaking at news conference in Moscow with several of Russia's venerated human rights defenders.

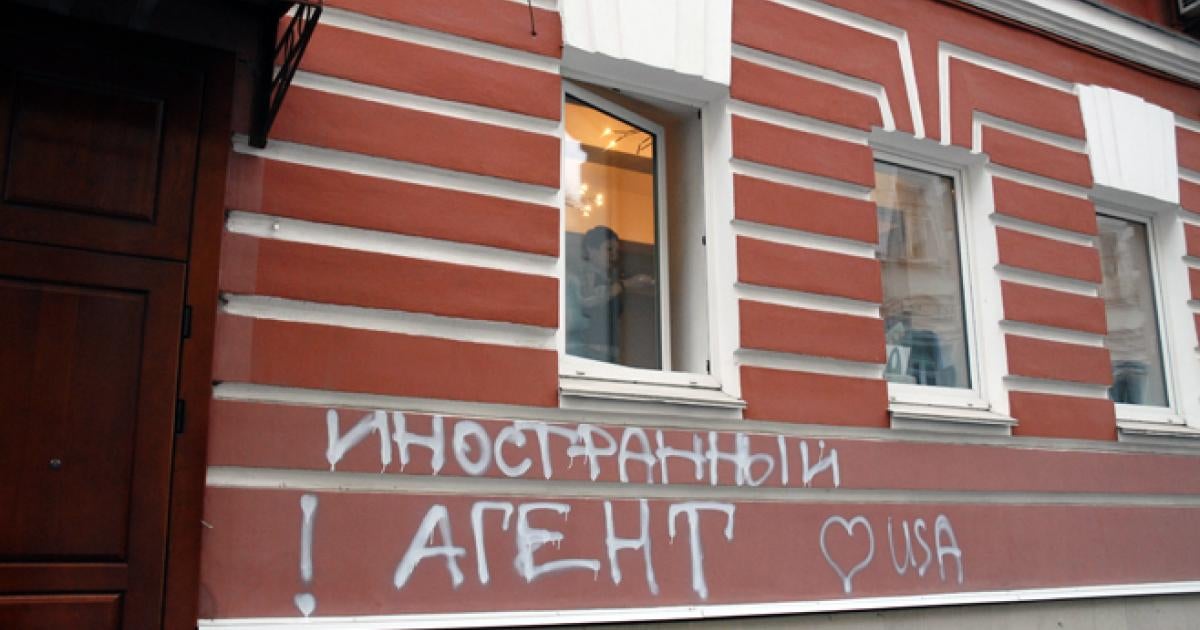

We were sounding the alarm that a draft law on "foreign agents," which Russia's parliament had just started debating, would be used to demonise independent voices. A week later, president Vladimir Putin signed the bill into law and Russia's human rights landscape has become almost unrecognisable since.

The foreign agents' law became the authorities' go-to malign tool for their war of attrition against civil society. In the years since, a number of other governments that are hostile to civil society have threatened to adopt copycat laws or parroted malevolent "foreign agent" rhetoric in campaigns against independent voices. To some observers, it might appear that Russia's leaders imposed silence and harsh censorship only since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. But in fact, the muzzling of Russian citizens is the result of a decade of step-by-step repression.

The original law required any non-governmental organisation that engages in any public advocacy, and accepts even a kopek of foreign funding, to place themselves on a "foreign agents" registry, submit duplicative, burdensome reports, and mark all materials with the stigmatising "foreign agent" label, which in Russia is tantamount to "traitor" or "spy." Later amendments allowed the government to forcibly register organisations and, eventually, individuals. At the time the government cynically claimed the law merely promoted funding transparency. Even early on, vitriolic public smear campaigns and a wave of nationwide "inspections" at the start of 2013 to ferret out "foreign agent" organisations, made clear that this law had nothing to do with transparency and everything to do with discouraging civic activism. Later, parliament sporadically expanded the law's scope to apply not only to just about any group or media outlet, but also to any individual, activist, blogger or journalist who publicly criticises the authorities and has some tenuous connection, no matter how tenuous, to foreign money. For example, simply participating in a training abroad is enough to make an individual a "foreign agent." New draft amendments now substitute the foreign funding requirement with the vague notion of "foreign influence." Further amendments have also increased penalties for individuals to up to five years in prison.

The full gamut of Russia's civil society groups have been hit with the law: those working on human rights, election monitoring, women's rights, the rights of migrants and asylum seekers, the environment, health—even a homeless shelter. Others designated as"foreign agents" were prominent YouTubers, political scientists, artists, and journalists. No infraction was too absurd for the authorities to penalise.

They took people to court for not adding the "foreign agent" label to social media posts made before the law was adopted and issued warnings for incorrectly displaying the "foreign agent" disclaimer, petty reporting errors, and not voluntarily registering as a "foreign agent." Civil society groups and individuals have had to waste countless hours preparing pointless, burdensome reports required under these laws. Individuals designated as foreign agents have to file regular reports on their personal expenses, including groceries, as well as any income.

They also spent countless hours in court and paid millions of rubles in fines and legal fees for specious violations. Some tried to adapt to the law, finding loopholes. A group that documents torture closed and re-constituted itself each time the Justice Ministry designated it. Other organisations, including even a group providing support to people with diabetes found the burden insurmountable and felt forced to shut down. Many activists and journalists left the country after being designated "foreign agents." When the justice ministry finally moved in 2021 to "liquidate" an organisation for violations of the foreign agent law it came as no surprise that its first victims were Memorial, the country's oldest human rights group, which commemorates victims of Soviet repression and its sister organisation, the Memorial Human Rights Center, which documents human rights violations in today's Russia. Violating these absurd laws and regulations can trigger felony criminal charges, making people live with the constant threat. For Semyon Simonov, who documented violations of migrant workers' rights in Sochi, it was more than a threat. After two years of criminal prosecution, in 2021 a court convicted him for not paying a "foreign agent" fine. Alexandra Koroleva of the environmental group "Ecodefense!" had to flee the country after five separate criminal cases were opened against her for not paying "foreign agent" fines. Russian authorities have many other tools they can use to silence critics, including vague "extremism" offences, bogus tax infractions, and the new war censorship laws. Why do they bother continuing to innovate and use their foreign agents' legislation? Most likely because of its utility in conflating independent thought and civic action with something that is foreign and harmful, and in excluding critics from public life. With rare exceptions, designated human rights groups are now shunned from engaging with government agencies, even those with which they had cooperated for many years. Experts, government officials and the like now hesitate or refuse to give interviews with media designated as "foreign agents." Amendments adopted in June propose extending this shunning, by banning "foreign agents" from involvement in educational and other public activities.

The authorities also use the foreign agents' designation process to mobilise public witch-hunts to parade out new "agents." In June, the European Court of Human Rights found that the law violates the right to freedom of association, and noted its chilling effect. But Russia left the Council of Europe in March and refuses to implement rulings issued since. A decade of insidious enforcement of the "foreign agents" law, and its auxiliary, the "undesirables" law, has led to the decimation of civil society space in the country. Russia's independent groups, in Russia and in exile, need support, through funding, visas, fellowships and the like. Since Russia left the Council of Europe, it's time to turn to the United Nations to re-establish a degree of scrutiny and pressure.

The UN's top human rights body, the Human Rights Council, can do so by appointing a dedicated human rights special rapporteur. This is an initiative the EU is the best placed to champion and lead. We've been sounding the alarm throughout the decade of government attacks on free speech. Now is the time to act.

Read the full article at the original website

References:

- https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/06/12/hungary-bill-seeks-stifle-independent-groups

- https://euobserver.com/opinion/154590

- https://www.codastory.com/disinformation/russias-foreign-agents-law-reverberates-around-the-world/

- https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/03/07/russia-criminalizes-independent-war-reporting-anti-war-protests

- https://www.hrw.org/news/2012/07/13/russia-reject-proposed-changes-rules-foreign-funded-ngos

- https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/11/25/russian-official-invokes-foreign-agent-law-bar-homeless-shelter

- https://newizv.ru/news/society/03-11-2021/pyat-let-tyurmy-za-smenu-avatarki-k-chemu-vedet-zakon-ob-inoagentah

- https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-foreign-agent-testimonials-putin/31524564.html

- https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/11/07/russia-helping-people-diabetes-foreign-agent-activity

- https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/07/12/russia-court-convicts-rights-defender

- https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/06/25/russia-environmentalist-faces-criminal-charges

- https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng#%7B%22itemid%22:[%22002-13687%22]%7D

- https://euobserver.com/world/154537

- https://www.hrw.org/news/2015/05/15/russia-stop-draft-law-undesirable-groups