The One Ring and the Villain in All of Us

This year marks the 20th anniversary of the release of the Fellowship of the Ring, the first part of Peter Jackson’s trilogy adapting JRR Tolkien’s Lord of Rings.

Next weekend is the Tolkien Society lectures. And later this year it’s possible Amazon’s Lord of Rings television series might be released.

All those things combined made me want to dig this essay out of the archives.

I wrote it a long time ago, before OffGuardian, when I had time to analyse films, and hadn’t quite been crafted into the hardened cynic of today.

Outside of writing fiction, pop culture analysis was what I wanted to do. Geopolitics may have become my arranged marriage, but I still fondly remember my first love.

The subject is, perhaps, more relevant than ever today. When the faceless, soulless nature of modern evil is growing more obvious every day. And when the “small acts of kindness and love” are more needed than ever before.

*

Meet Alan Howard.

Not meaning to sound like a hipster, but you have probably never heard of him. It could be the name sounds faintly familiar. Maybe you saw him in that thing, you know? Years ago? With that woman? He was really good in it. What was it bloody called? Ah, that’s gonna drive me crazy!

Anyway, he’s a solid, classically trained character actor. He was in The Cook, the Thief his Wife & Her Lover (1989), he played Oliver Cromwell in the not-as-bad-as-everyone-says Return of the Musketeers (also 1989) and more recently played the father in Parade’s End opposite the ubiquitous Benedict Cumberbatch.

He also did the voice of The Ring in The Lord of the Rings trilogy.

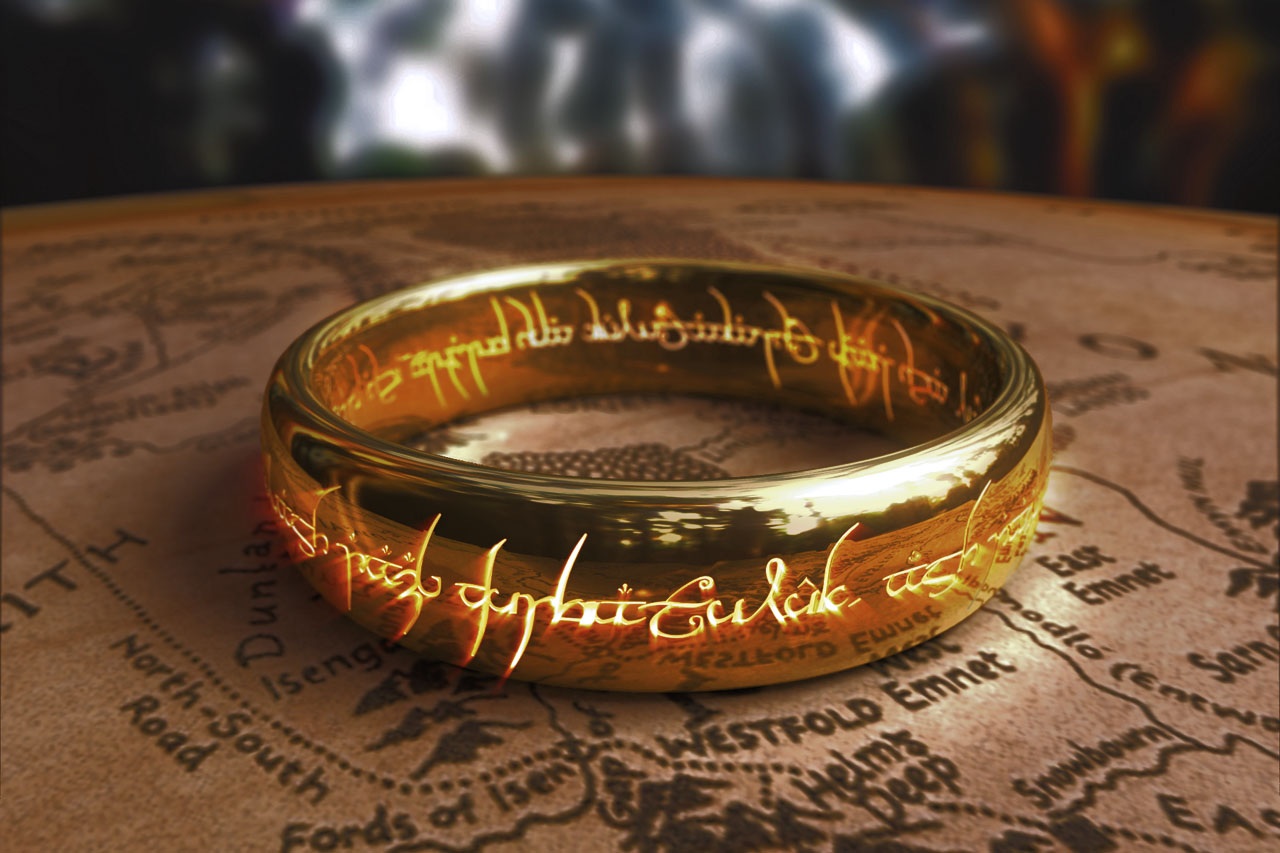

Think about that…The Ring had a voice. It seems strange to say it out loud, yet we all just accepted it without question while watching the films. Who is the villain of the trilogy? Sauron, of course. But he is nothing but a distant presence. A giant flaming eye, seen in small snatches. He has no voice, no face.

It is a triumph of storytelling that director Peter Jackson can keep you watching a movie for 10+ hours, despite it having no true antagonist. No real villain. Except The Ring.

The Ring is the most prominent and threatening source of villainy present in the films, and yet all it does is sit in the hero’s pocket and whisper. It is this, the ephemeral nature of the evil in The Lord of the Rings (hereafter LotR), that I want to explore.

If you own the Special Extended Edition of The Fellowship of the Ring (2001) (which you should, because it’s fantastic) then you have probably watched the DVD extras (which are also fantastic). The first program, “JRR Tolkien: Creator of Middle Earth”, makes some interesting points about the nature of evil as depicted in LotR.

Tom Shippey, Oxford Don and Tolkien biographer, analyses a short scene early in the film. In this scene Gandalf (Ian McKellen) is encouraging Frodo (Elijah Wood) to hide the ring away and never use it.

“Keep it secret. Keep it safe,” he says. Extending an empty envelope and waiting for Frodo to simply drop the ring in. Frodo waits. His face anxious. Suddenly, letting the ring go is difficult. The book describes it as becoming immensely heavy in Frodo’s hand.

The interesting question therefore becomes: Why does the Ring feel heavier?

To paraphrase Dr Shippey’s analysis of this: One of two things is occurring here. Either Frodo’s subconscious is feeling the ring as heavy because, deep down, he is reticent to give it up. If that’s the case then the Ring’s power is internal. It can influence your decisions, your state of mind. The second possibility is that Ring simply has its own magical sentience. It can make itself heavier, it has a will of its own. In that instance its power is external.

However, if the Ring’s power is solely external, how much of a threat does it truly pose? Anybody could carry it without ill effects. Anybody with good intentions and a mind of their own could be the hero.

We are told over and over that this is not the case. Gandalf, Galadriel (Cate Blanchett), Aragorn (Viggo Mortensen). All, at one point or another, feel the lure of The Ring’s power. All know they should resist that temptation. Gandalf and Galadriel explicitly warn Frodo of the “great and terrible” power the ring would “wield through them”.

Tolkien makes it quite clear: Good intentions won’t save you from the pervasive evil of the Ring. The threat of The Ring hides in the dark recesses of your ego and your own ambition.

In place fo the Dark Lord you would have a queen, not dark but beautiful and terrible as the dawn…

This is, perhaps, why Hobbits have such a “remarkable resistance to its evil”. Innocent creatures content with simple things. They not only lack power, but harbor no secret ambitions. They are happy to affect the world in what small, pleasant ways they can. It’s worth noting that the only two characters to EVER give up The Ring voluntarily are Hobbits, (Bilbo and Sam).

So what exactly is The Ring?

Tolkien famously despised allegory, favouring what he called “applicability”. The latter, he said, resides in the freedom of the reader and the former the purposed domination of the author. Perhaps his reluctance to in any way “dominate” the minds of his readers is expressed in the vagueness of the Ring as an entity.

We’re never sure exactly why or how it does the things it does. We never know the limits, if there are any, to its magic. In Jackson’s films this is further highlighted. The size, shape and weight of the ring are all fluid. Nothing about it is definite. Only one word is ever concretely linked to it: Power. The Ring has power. The Ring is power.

The effects of this power are keenly felt, sharply observed, and subtly portrayed across a wide spectrum of characters through all three Lord of the Rings films and into the first two parts of The Hobbit. Vainglorious men like Deneathor (John Noble), brought low by despair, become monsters. Wise but ambitious Saruman (Christopher Lee) turns Quisling for scraps of power. Boromir (Sean Bean), a strong man and decent to his core, is crippled and twisted by fear.

Gollum, perfectly realised by Andy Serkis, is perhaps Tolkien’s most complex and original creation. He serves as a warning to us throughout Two Towers and Return of the King. The ravages of the Ring show through his thin hair and pale skin and cracked smile.

“You were not so very different from a Hobbit once,” Frodo tells him in the second film. And we see this for a fact in the sad and brutal flashback that kicks off the third instalment. He was once content to sit and fish the river with his cousin. And now? Now he has “forgotten the taste of bread, the sound of trees. He has even forgotten his own name.” If such an apparently simple creature can succumb to easily, what chance does Frodo stand? What chance do we stand?

Even gentle, kindly Bilbo (Martin Freeman/Ian Holm) is not totally immune. In The Hobbit: Desolation of Smaug (2013) we see him savagely cut down a seemingly benign creature for the sake of his new bauble. When he darkly and triumphantly declares “Mine!” through a mask of spattered blood, a chill goes down your spine as you are reminded of that moment in Fellowship. When, for a heartbeat, the mask slips and you’re confronted with the darkness that Bilbo’s strength of character has held at bay for sixty years.

The most potent symbols of the Ring’s malign influence are the Nazgul, or Ringwraiths. The book tells us little about them, the films even less. We know they were once nine “Great Kings of Men” who were tricked by Sauron, who played on their greed, and one by one they “fell into darkness”. We’re never told exactly what that means.

They have no voice anymore, no face. No hopes or desires or hatreds. “They are neither living nor dead.” says Aragorn in Fellowship “Drawn to the power of The Ring. They will never stop hunting you.” All of these things create an image of shape without a soul. A husk of a being with purpose where a heart should be.

All of Tolkien’s personifications of evil are defined in that same way: by what they have lost. By what they used to be, rather than what they are. Gollum used to be Smeagol. Wormtongue “was once a man of Rohan”. Saruman was the greatest and wisest of the Wizards. Orcs used to be Elves. The Devil was an angel once.

In Tolkien’s works, evil is a vacuum, defined by absence. Just as darkness is only an absence of light.

Tolkien, of course, was a veteran of World War I. And who knows how that changed him or his outlook on things. We know he lost virtually all his close friends in what is largely regarded (and was even at the time) as a massive waste of time, and money, and young lives. It achieved nothing, visited terrible times on innocent men and their families, and yet it droned on. Why? Because the people in charge had “fallen into darkness”.

The more common picture of evil is, perhaps, rather childish in comparison. The cartoon bad guy who simply enjoys being mean. The sadistic psycho who gets his kicks peeling off people’s skin. The Bond villain who rejoices in being bad. The cackling witch who’ll get you and your little dog too.

It’s almost reassuring to think of villains that way. Caricatures who possess traits we can’t imagine in ourselves. But that’s not the real nature of true evil in the modern world. Evil is beyond sadism, beyond malignity. The greatest evils of our time weren’t done with wicked smiles, but by the sigh of a work-a-day clerk.

The nature of evil in the twentieth century is (as Dr Shippey puts it) “curiously impersonal.” Bureaucrats signing over millions of lives with the flick of a pen. Presidents flattening whole cities with the push of a button. Politicians and civil servants chatting over coffee, as they start a war that lasts ten years.

More specific recent examples are NHS trusts shuttering their A&E departments for no purpose. Politicians voting through bills that render tens-of-millions unemployed. Doctors signing DNR orders for the autistic or mildly frail. Guidelines forcing ventilator tubes down throats all across the world.

Not because they think it’s right, not even because they secretly enjoy being wrong. They don’t see right or wrong any more. Only opinion polls and balance sheets. They serve the machinery of power now, and have lost themselves completely. Morals have become nothing by stones on an abacus.

That is what it means to become a wraith, and no longer be either living or dead. That is how you fall into darkness. That’s the troubling image of evil that Tolkien and Jackson present to us.

The casting of Alan Howard to voice the ring was a brilliant move by Peter Jackson (and the other writers/producers). It accomplishes something important: it adds menace to an oddly villainless story. It adds a solid, corporeal counterweight to a plot filled with memorable heroes. Respect must also be paid to Howard Shore’s genius use of music. The Ring’s theme, something you’d expect to be menacing, is this elegiac piece. Full of age and sadness. Almost a siren’s call. “Come with me,” it seems to say. Promising to return you to some safe dream you had long, long ago.

The use of music and voice merge to give The Ring a presence in the films. It broods over everything, a dark cloud of energy. But energy and presence are not character. The Ring isn’t literally alive. The Ring isn’t a person with direction, it is simply the void calling you home. Inviting you to be the worst version of yourself.

In that sense, the fantasy world of an old Oxford don holds something very real, and very unsettling. To quote Dr Tom Shippey one last time:

People say this fantasy fiction is escapist and evading the real world, well I think that’s an evasion. The Lord of Rings is trying to confront something most people would rather not confront. ‘It could be you.’ It’s saying. And under the right circumstances, it WILL be you.”

Maybe that fell in line with Tolkien’s religion, the idea of being born pure and the soul becoming corrupt. Maybe it’s just the way he saw the world, as an old man having lived through some dark times.

Through Tolkien’s books and Jackson’s films we are confronted with our own ability to indulge the worst parts of ourselves. The chance we will become the villain. And while this makes us shuffle uncomfortably in our seats, it should also empower us.

If Evil is small. If villainy is nothing but a weakness of mind and a lack of compassion and empathy. If we can see through its grandiose self-image to the degraded thing it really is, it becomes easier to fight.

That message of hope is beautifully stated in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey (2012):

Saruman believes it is only great power that can hold evil in check, but that is not what I have found. I found it is the small everyday deeds of ordinary folk that keep the darkness at bay… small acts of kindness and love.”

An important message, for our time and all time.

SUPPORT OUR WORK

Read the full article at the original website

References: