Data vs. Dance: Approaches to complex systems

As much as any of us might like to tell ourselves that age is just a number, some of those numbers tend to stick out and feel more significant than others. They have a way of making us pause and reflect. As I write this I am approaching a d

As much as any of us might like to tell ourselves that age is just a number, some of those numbers tend to stick out and feel more significant than others. They have a way of making us pause and reflect. As I write this I am approaching a divisible-by-ten birthday, turning 30, and lately I’ve been reflecting on the phases of my intellectual development over the last ten years.

At the time of my last decadal transition I was your typical college student, perhaps apart from the fact that I had just started to claim intention and ownership of my learning. I had transferred from the undergraduate business school into an economics major after becoming disillusioned with the courses and culture. It was a small shift in the grand scheme of things but meaningful for me, as I was no longer on the path of least resistance.

Since then, my love of learning has taken me on deep dives into environmentalism and data science, and to toe-dips into philosophy, mathematics, energy, ecology, cultural evolution, and a smattering of other fields. But one of my first big splashes after completing my undergraduate was into complex systems science.

Complex systems science (or “complexity science”) is a fascinating interdisciplinary academic field with a simple idea at its core. Instead of seeking to understand the world by breaking things down into their constituent parts, let’s see what we can learn by studying wholes, centering relationships, and keeping context in mind. As it turns out, this simple idea is pretty subversive to modern intellectual thought, although it can be hard to see the extent to which science and culture have been shaped by the dominance of the break-it-down epistemology (often referred to as “reductionism”).

In economics, “the market” is broken down into consumers and firms, each of which are modeled as disconnected automatons, whose only interaction is to influence one another through their effects on prevailing prices. In medicine, we understand the human body and experience as consisting of distinct organ systems, distinct developmental phases, and distinct things that can go wrong, and we have specialists for each. Even in something like basketball we think the game has distinct elements, offense and defense, spacing and shot-making, consistency and poise. In all these examples, and in countless other places we might look, it is easy enough to see that the lines we draw are conventions, abstractions, products of the mind. These divisions can be useful, and without them we might feel lost. But in truth, everything is connected, and we are surrounded by complex systems.

The following excerpt from Jonathan Rowson’s book The Moves That Matter: A Chess Grandmaster on the Game of Life does a nice job capturing the fact that we are always swimming in interconnected systems:

“Systems thinking can seem niche and exacting, but systems are not exotic, they are within and between everything. The solar system includes Earth’s atmospheric system. We organise our lives on this planet through a political system which tries to govern an economic system, which relies on material resources provided by natural systems, and also on the perpetual creation of consumer demand through a semiotic system of persuasion called marketing. Marketing works on our nervous systems to increase our desire for all sorts of things we don’t need but might like, for instance, doughnuts enhanced with pearl sugar, strawberry jam, pink icing and Madagascar vanilla cream. These unreasonably tasty doughnuts subvert our appetite control systems that evolved with a weakness for densely caloric food to aid short-term survival, particularly under stress. A shift in demand for such doughnuts at scale impacts upon related supply chains and ecosystems in ways we never suspect while licking tasty remnants from our lower lips. Over time, systemic influences reinforce cravings for doughnut-like products in obesogenic cultures which eventually destroy our immune systems, our health systems and the ecosystems on which life as such depends. The breakdown of systems that aid our quality of life caused by a confluence of other systems is partly why activists speak of ‘the system’ as a whole, and don’t necessarily refrain from eating doughnuts. Instead they say: ‘We have to change the system!’”

The countercultural element of systems thinking and particularly complex systems science was undeniably attractive to my sensibilities, but even more attractive was that it works. An early example of this (which actually predates the nomenclature of “complexity”) was The Limits to Growth, released in 1972. MIT researchers funded by the Club of Rome used a novel “systems dynamics” simulation to map the interaction of planet-level trends in population, food production, industrialization, pollution, and consumption. This groundbreaking work provided a foundation for what has become a simple truth of the environmental movement: that limitless industrial growth on a finite planet like our blue-green earth is impossible.

Another fascinating feat of complex systems science came in 1997, when Geoffrey West, James Brown, and Brian Enquist published a theory (WBE theory) explaining previously observed scaling patterns across species. Mostly likely you have never wondered about the extent to which an elephant is just a scaled-up version of a mouse, but it turns out that extent is pretty large. These scientists sought to explain the remarkable predictability in the relationship observed between mass and metabolic rate (Kleiber’s Law). In simple terms, the WBE theory showed that the mouse and the elephant share a common branching pattern in the geometry of their circulatory systems (“fractal geometry”), and this commonality across species which produces the scaling relation. This may sound like an extremely niche story of an academic breakthrough, but the consequences of understanding the mechanisms at work are far-reaching, as captured in the full title of West’s 2018 book Scale: The Universal Laws of Life, Growth, and Death in Organisms, Cities, and Companies.

My own foray into complex systems science didn’t produce any such breakthroughs. Not even close. But it did help broaden my view of the world. I took advantage of free online courses offered by the Santa Fe Institute and learned about fractal geometry, nonlinear dynamical systems, agent-based modeling, and a few other topics. In addition to Geoffrey West’s book I read work by Robert Axtell, W. Brian Arthur, Fritjof Capra and Pierre Luigi Luisi, and when the Sante Fe Institute published edited volumes, I eagerly scooped those up as well.

One of those volumes is called Worlds Hidden in Plain Sight: Thirty Years of Complexity Thinking at the Sante Fe Institute, edited by David Krakauer, the current president of SFI. I had originally read it in my early- to mid-twenties, but when packing for a recent trip, I found myself between books and decided to throw it into my backpack to revisit on the plane. This volume contains essays tracking the emergence and growth of complex systems science from the 1980s to the present. While I expected a relaxing trip down this intellectual memory lane, what I found in those pages actually surprised and bothered me. The content hadn’t changed since I first read the book, but something about my perspective certainly had.

Here are some examples of the phrases that were irking me, often found in or near the conclusions of these essays.

In an essay titled Engineered Societies, after discussing the massive amount of available data on human social interaction via social media these days, authors Jessica C. Flack and Manfred D. Laubichler state:

“[W]ithin the data (if appropriately anonymized) is immense potential for gaining fine-grained insights into social patterns and designs as, increasingly, people from all walks of life are living online lives.”

In another, this one titled What Happens When the Systems We Rely On Go Haywire?, author John H. Miller concludes with:

“We find ourselves in a race for knowledge and control of the complex world around us, a race that we must win if we are to thrive, and perhaps even survive, as a species.”

Finally, in an essay titled Learning How To Control Complex Systems, we hear from Seth Lloyd that

“as one goes to finer and finer scales, and to more and more frequent sampling, a scale may arise at which an uncontrollable system suddenly becomes controllable.”

Later, he notes that

“[t]o characterize and control our surroundings, we must identify the parts of the world where order can be increased at the expense of disorder.”

Can you spot the pattern here? There is a tendency among these authors to identify highly complex and dynamic phenomena, and to frame that complexity as a challenge to be met with enormous data and computation. If only we had a big enough supercomputer or a smart enough artificial intelligence we could run a more accurate simulation and achieve control of what is currently uncontrollable. The problem I see here is that in setting their sights on control, these authors betray the nature of complex systems science and make the mistake humanity has been making for hundreds (if not thousands) of years. If you ask me, it is our lust for power and control over nature that is coming around to bite us.

I suppose there are three possible responses when one confronts the complex interconnectedness of the world around us and comes to accept that nature is inherently entangled. You can do as these authors do, and place your bets on Moore’s Law (big data and computation) to unravel the mysteries of complex systems. This is an unwise strategy, and I’ll give a few reasons why in a moment. Another option, always available but never preferable, is to give up on knowledge. We will never fully grasp the world in our hands, to do with as we please, so what’s the point? A third option is, in the words of Limits to Growth author Donella Meadows, to dance with systems.

But before we put our dancing shoes on, let me say a bit more about why the road that runs through big data to reach understanding and control is a treacherous one.

First, energy. I mentioned Moore’s Law, which is the pattern of exponential digital technology whereby the number of transistors on a computer chip has been doubling at a near-constant rate of about two years for the last several decades. This is the pattern that has launched us into the information age, but despite what we might hope, it has not freed us from the material and energetic constraints of physical reality. If you are relying on this pattern to sort out complexity and provide control, you are betting on ever-increasing availability of massive computation, which depends on the very physical elements of electricity, rare metals and other material inputs, and extremely complex supply chains. That’s not to mention the water needed for cooling massive data centers, and so on. In other words, computation is a product of high-energy modernity, which has been shown repeatedly to be unsustainable. A recent approach to this idea that I found extremely clear and accessible is Tom Murphy’s Metastatic Modernity series.

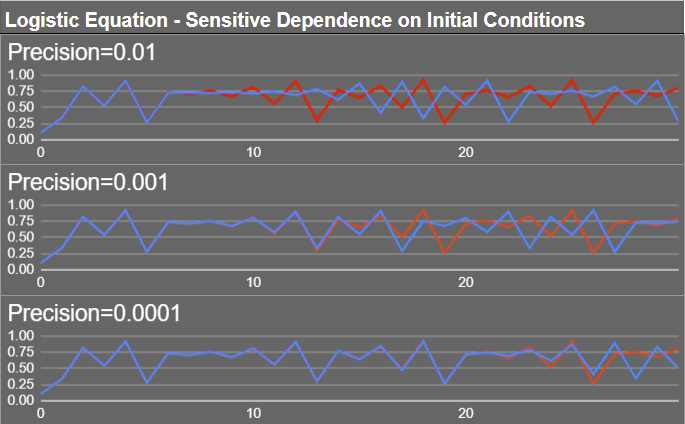

Second, chaos. Let’s assume access to computation is not a problem. Complex systems exhibit chaotic behavior, and it isn’t difficult to show why this creates an intractable problem for the predict-and-control approach. Consider the logistic equation, which is a mathematical relationship used to demonstrate chaos. The equation states that the value at any given time step can be calculated by a simple transformation of the value at the preceding time step, and given this simplicity, you might think it is easy to predict where the value ends up if we simulate forward, say, ten time steps. If you know the initial value with complete precision, that would be correct. But if we plug in an estimate of the initial value and we are off by a teeny tiny amount, our prediction can be way off from reality just a few steps down the road. And as you extend the time period that you want to predict, the amount of precision you need in measuring the initial condition increases exponentially. Here and here are a couple of good resources if you want to learn more, but the point is this: if you are hoping that the age of AI and big data will help us cross thresholds where complex systems go from uncontrollable to controllable, you are essentially chasing one exponential (chaos) with another (Moore’s Law). I have a pretty strong feeling about which of those will win out.

The logistic equation demonstrates the sensitive dependence on initial conditions in chaotic systems. Orders of magnitude increases in precision result in relatively small increases in predictive capacity.

Third, entropy. The Second Law of Thermodynamics describes the tendency for energy to spread out over time from more useful, concentrated bundles to less useful, distributed messes. (Why does energy do this? I’d recommend this video for an explainer.) Systems with low entropy, where energy is more compact and useful, take less information to describe, and are therefore easier to control. But given the Second Law, in order to reduce the entropy in one area, entropy must be increased elsewhere. Refrigerators, flame, and life itself are all intuitive examples of this: the refrigerator dissipates heat to keep itself cool, a flame combusts its source, and life expels disorder in all sorts of ways. As a result of the Second Law, if you attempt to solve a problem like climate change by controlling the complex systems that drive it, you may find yourself playing whack-a-mole as unintended disorderly consequences pop up in connected systems. Perhaps you solved carbon emissions, but crashed the economy and crushed biodiversity. This is why systems thinkers tend to speak in terms of “responses” rather than “solutions” — because our “solutions” don’t tend to stay within our arbitrary boundaries, and often come back around to bite us.

Fourth, the observer effect. If you seek control of complex systems, you are necessarily assuming a separation between the controller and the thing to be controlled. You’re in good company, as this is how science typically operates, with a hard separation between the observer and the observed. But we know that fundamentally that separation does not exist, and in fact reliance on it betrays the core insight of complex systems science. There are some things you just can’t understand unless you engage with them. This insight is well-developed by Robert Pirsig in his novel Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, in which the main character comes to see the notion of “working on his motorcycle” as a poor framing. A better framing is to see him and his motorcycle as a connected system working together towards quality.

Hopefully at this point you’re wondering about “dancing with systems.” I would direct you to Donella Meadows’s essay of the same name, and I would really recommend taking some time to read it. But you might get the core idea just from the title: We need to treat complex systems not as objects we can predictably control, but as partners in a great dance. You can nudge and hint at the next move, but you can’t fully determine it, and if you’re any good you’ll be able to receive feedback and adjust your behavior as well.

Of course, whether you have dancing experience or not, we’re almost all experts at this kind of interaction. Unless you’re an economist, you don’t collect huge amounts of data on your romantic partner and use it to predict and ultimately control how they’ll respond when you ask what they’d like for dinner. (Incidentally in my case, I wouldn’t need big data to tell me what my wife wants for dinner; the answer is almost always “soup.”) Any healthy relationship is a give and take, with risks, surprises, and mutual growth along the way. The same goes for all our relationships, including with the natural environment around us.

And yet, despite our familiarity with this “dancing,” it remains contrary to normal scientific practice, and I think it’s this opposition of forces that makes complex systems science generative and interesting. In one direction, science insists upon separation and objective observation. In the other, reality begs for connectedness. The phrase “modeling complex systems” captures the inherent compromise, as it implies a sharp disconnection between the modeler and that which is modeled, while within the model elements are connected and allowed to interact.

Through recognition of this compromise and the limitations it imposes, a working knowledge of complex systems science can be a good antidote to the pervasive but flawed cultural narrative that science and technology are the sole saviors to our current global predicaments. That has been my experience, at least. Since learning about complex systems science, my intellectual journey has taken me on a path toward better appreciation of experiential, participatory knowledge in partnership with scientific knowledge. As Robin Wall Kimmerer notes in her best-selling book Braiding Sweetgrass, “science does not have a monopoly on truth.” Kimmerer and other indigenous authors have explored how indigenous cultures are worth learning from in part because (to paint in broad strokes) they have kept connectedness to the natural world at the center of their cultural knowledge systems.

With all that said, as a data scientist I certainly understand the allure of capturing mountains of information and extracting insights, making predictions, and optimizing for control of complex systems. But I also know that more data isn’t always better, and often the best interventions create feedback loops where the right information gets to the right people at the right time, enabling continuous learning and improvement. Instead of imposing control on the complexity “out there,” we can nurture the complexity “in here” to get better at listening, learning, and responding. Sometimes we don’t need more data, we just need to get out there and dance.

I hope I’m able to break out a few new moves in my thirties — just don’t expect to see me breakdancing at my 40th birthday party.

Read the full article at the original website

References:

- https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/40653130-the-moves-that-matter

- https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/647942.The_Limits_to_Growth?ref=nav_sb_ss_2_16

- https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/31670196-scale?ref=nav_sb_ss_3_5

- https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/45700960-worlds-hidden-in-plain-sight?ref=nav_sb_ss_2_28

- https://sfiscience.medium.com/engineered-societies-7a8146d44260

- https://www.csmonitor.com/Science/Complexity/2016/0919/What-happens-when-the-systems-we-rely-on-go-haywire

- https://dothemath.ucsd.edu/metastatic-modernity-video-series/

- https://www.space.com/chaos-theory-explainer-unpredictable-systems.html

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ovJcsL7vyrk&t=658s

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DxL2HoqLbyA&t=588s&pp=ygUSdmVyaXRhc2l1bSBlbnRyb3B5

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10423648/

- https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/629.Zen_and_the_Art_of_Motorcycle_Maintenance?ref=nav_sb_ss_1_24

- https://donellameadows.org/archives/dancing-with-systems/

- https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/17465709-braiding-sweetgrass?from_search=true&from_srp=true&qid=BrM3vW55jo&rank=1

- https://unsplash.com/@aoddeh?utm_content=creditCopyText&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=unsplash

- https://unsplash.com/photos/dancing-woman-on-concrete-pavement-JhqhGfX_Wd8?utm_content=creditCopyText&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=unsplash

- https://bsky.app/intent/compose?text=Data%20vs.%20Dance%3A%20Approaches%20to%20complex%20systems+https%3A%2F%2Fwww.resilience.org%2Fstories%2F2025-03-24%2Fdata-vs-dance-approaches-to-complex-systems%2F

- https://x.com/intent/tweet?text=Data%20vs.%20Dance%3A%20Approaches%20to%20complex%20systems&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.resilience.org%2Fstories%2F2025-03-24%2Fdata-vs-dance-approaches-to-complex-systems%2F

- https://www.linkedin.com/shareArticle?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.resilience.org%2Fstories%2F2025-03-24%2Fdata-vs-dance-approaches-to-complex-systems%2F&title=Data%20vs.%20Dance%3A%20Approaches%20to%20complex%20systems&summary=Instead%20of%20imposing%20control%20on%20the%20complexity%20%E2%80%9Cout%20there%2C%E2%80%9D%20we%20can%20nurture%20the%20complexity%20%E2%80%9Cin%20here%E2%80%9D%20to%20get%20better%20at%20listening%2C%20learning%2C%20and%20responding.%20Sometimes%20we%20don%E2%80%99t%20need%20more%20data%2C%20we%20just%20need%20to%20get%20out%20there%20and%20dance.&mini=true