Mutual Aid: Lessons from East Boston

This is a special bonus episode of the Cities@Tufts podcast! Last fall, Tufts University Distinguished Senior Lecturer of Urban Environmental Policy and Planning, Penn Loh, hosted a discussion following the release of a new report, Mutual A

This is a special bonus episode of the Cities@Tufts podcast!

Last fall, Tufts University Distinguished Senior Lecturer of Urban Environmental Policy and Planning, Penn Loh, hosted a discussion following the release of a new report, Mutual Aid Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic: Strengthening Civic Infrastructure in East Boston through Community Care.

This episode is from that live event, hosted by Tufts UEP, on October 3, 2024 where panelists shared their mutual aid experiences, lessons learned, and other key findings from UEP-community report on how mutual aid can strengthen civic infrastructure, contribute to movements for social justice, and build communities of care.

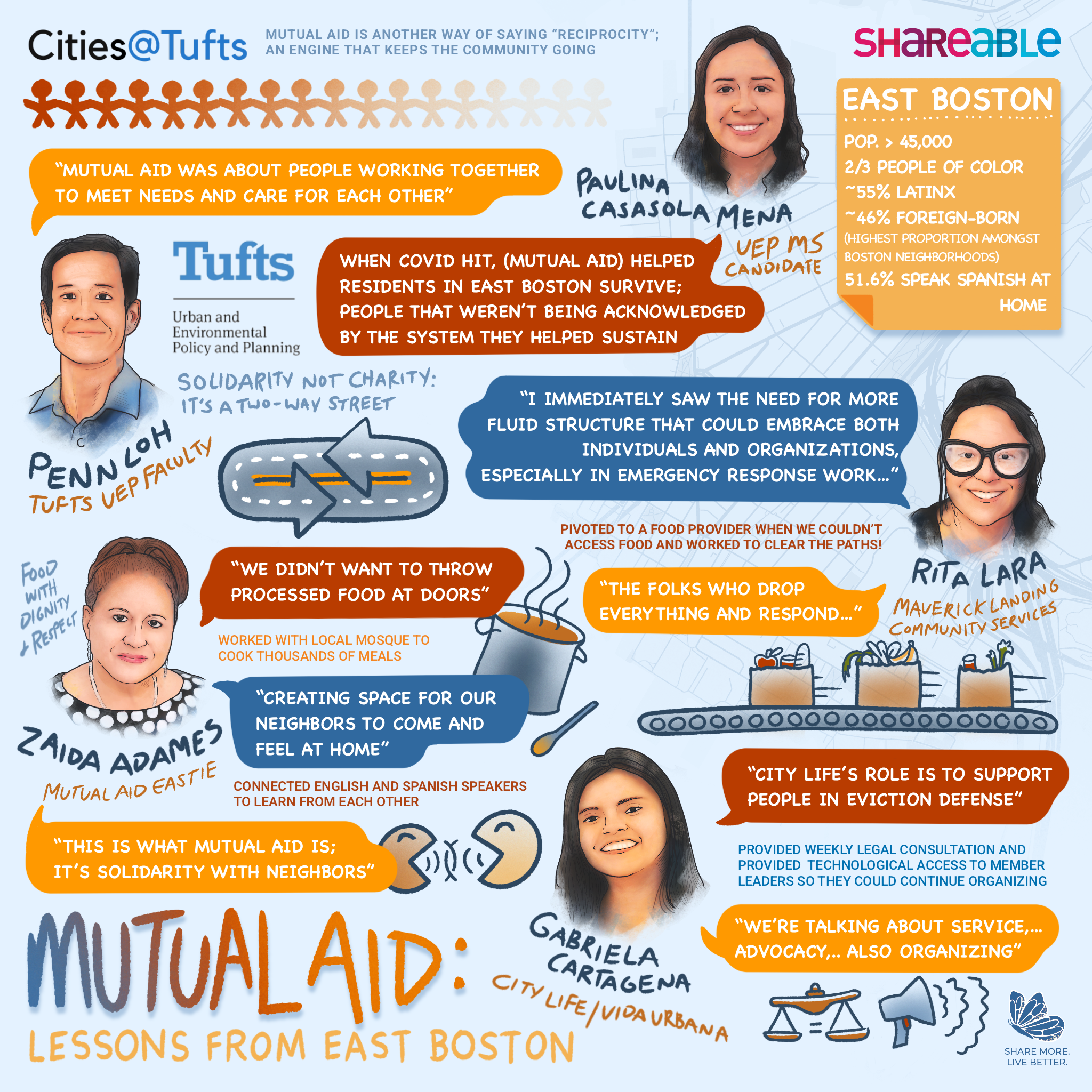

Graphic illustration by Jess Milner.

If you’re a follower of Shareable’s other programs, you may have noticed that we’ve also been supporting an initiative in East Boston for the past year, with several members of Mutual Aid Eastie participating in our Libraries of Things Fellowship.

If this episode inspires you to be better prepared to care for your communities, you should check out Shareable’s free four-week Mutual Aid 101 learning series that starts next month. This learning and action webinar series will draw on the experience of mutual aid organizers and activists across the U. S. to educate and resource people who are ready to build or strengthen networks of care and resistance in their local communities. The series runs on four Wednesdays from February 19th to March 12th at 4:00 PM PT/7:00 PM ET.

Listen to Cities@Tufts wherever you get your podcasts:

Transcription

0:00:09.0 Tom Llewellyn: Welcome to another episode of Cities@Tufts Lectures, where we explore the impact of urban planning on our communities and the opportunities designed for greater equity and justice. This season is brought to you by Shareable and the Department of Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning at Tufts University with support from the Barr Foundation. We’re back after our winter break with another set of open lectures. The Spring 2025 Colloquium features topics like solidarity, economies at the urban level, environmental racism in Canada, and cultural politics in Barcelona. Click the link in the show notes to register for each event. Today on the show we have a special bonus episode for you. Last fall, Tufts University Distinguished Senior Lecturer of Urban Environmental Policy and Planning, Penn Loh, hosted a discussion following the release of a new report, Mutual Aid lessons from the COVID 19 pandemic strengthening civic Infrastructure in East Boston through Community Care. If you are a follower of Sharable’s other programs, you may have noticed that we’ve also been supporting an initiative in East Boston for the past year with several members of Mutual Aid Eastie participating in our Libraries of Things Fellowship. If this episode inspires you to be better prepared to care for your communities, you should check out Shareable’s free 4 week Mutual Aid 101 training that starts next month.

0:01:28.5 Tom Llewellyn: This Learning in Action webinar series will draw on the experience of Mutual Aid organizers and activists across the US to educate and resource people who are ready to build or strengthen networks of care and resistance in their local communities. The series runs on 4 Wednesdays from February 19 to March 12 at 7pm Eastern, 4 Pacific. Each 90 minute session can be joined individually or you can sign up for the full set. There’s a link in the show notes and you can also visit shareable.net to register or to see the growing list of speakers including noted Mutual Aid organizer and author Dean Spade who will be leading our first session. And now let’s get to today’s discussion. Here’s our guest host, Penn Low.

0:02:13.3 Penn Loh: Welcome. Really great to see everybody. You have made it to our session here called Mutual Aid Lessons from East Boston. Thanks for coming here and joining us today. I want to first thank a number of folks who made today possible. We have a whole slew of UEP graduate students who have served as research assistants on this project. Not all of them are able to be with us at the moment, but I’ll just call them out by name. We had Melissa Cepeda, Melissa Velazquez, Elisa Guerrero, and then in the room here we’ve got Isabella Buford and Paulina Casasola. So thank you to our research assistants who’ve been on this project. I also need to thank AmeriCorps. AmeriCorps is the agency that supports all kinds of civic engagement opportunities, and they also support community research. And so we’ve gotten support for the last number of years to support projects including this one. And I’ll say a little bit more about that project. I’m also seeing a number of folks from Tisch College in here. I want to acknowledge the Tisch College here at Tufts. The Tisch College for Civic Life has been a great partner with our department, the Department of Urban Environmental Policy and Planning, and specifically to support a lot of the community partnership work that I’ve been involved in, of which this is a part. Yeah. So thank you so much for being with us.

0:03:38.6 Penn Loh: So why are we involved in exploring Mutual Aid? This came out of previous work. So we had the, I won’t say the long story, but the short story is that we had already been in a partnership that was supported by AmeriCorps that was studying community based planning. And that’s when the pandemic hit. And when the pandemic really shut everything down, AmeriCorps made another year of funding available, including exploring topics that were related to the pandemic. And so that’s when we said, you know what? All of our community partners are just have significantly been impacted, changed up what they’re doing, how they’re doing it, how they’re connecting to their communities. And let’s take a moment to try to learn from that experience. And so the report that you see up there called Grounded and Interconnected in the Pandemic was the prior project. We had eight different groups that are shown up there that all participated, who came together to share, reflect with one another. And one of the findings coming out of that was that almost all the groups, they all 100% of them, shifted to doing work related to direct aid in their communities. And that’s not a surprise, given the need and given how these groups are set up and their connections to oftentimes the most vulnerable communities.

0:05:05.2 Penn Loh: However, a number of them were also trying to do this work in a way that they called Mutual Aid. And they were very excited about the prospects of a Mutual Aid approach. And again, I’ll just say a little bit about what were some of the things we were learning there. That Mutual Aid was about people working together to meet needs and care for each other, that Mutual Aid could be a way of doing civic engagement, that it was an important part of the civic kind of infrastructure. And social capital in a community, that it was a really important part of community resilience. The pandemic being a very profound example of experiencing impact and trying to figure out how to survive through that. However, Mutual Aid is not the same thing as social services or direct aid. And in fact, a lot of people who do Mutual Aid want to do it because they talk about this as being solidarity, not charity. Right. Mutual Aid implies that there’s some type of reciprocity, that there’s a two way street, not just resources flowing one way. There are a lot of debates about this and we can get into them with the folks that we’ve invited here today.

0:06:11.6 Penn Loh: Some folks look at Mutual Aid as something that helps survive crises. It’s only temporary. Then there are others, including a lot of the folks we’re here with today, who see this as maybe a permanent way we should be organizing ourselves. There are also a lot of debates over how can and should government funders, other existing social service agencies be a part of these processes. And some folks are maybe less optimistic about that. Other folks are like saying, hey, we can give it a go and see what happens, right? And that we’ve learned some things from what happened during the pandemic. We’re going to do a very quick review just of East Boston. It’s a working class community, large concentration of immigrants, particularly Spanish speaking immigrants, and as well as many other people of color and a lot of immigrants. This is a neighborhood, over 45,000 people, two thirds people of color, majority Latinx. And this is the neighborhood that has the highest percentage of people who are foreign born in Boston. And it was one of the areas that was the hardest hit by Covid. The maps are just showing where East Boston is in relation to Boston.

0:07:16.8 Penn Loh: Those of you who don’t know Boston, not sure why it’s east when it’s like north, right? North. The north end is actually south of East Boston. South Boston is a little bit more east of East Boston. Anyway, these little symbols here, we did a lot of work to try to document what does the civic infrastructure look like. And these are just some of the dots representing the different types of community organizations that are in East Boston. So the project that we did for this time, and I’ll do a little bit more formal introduction of our partners. So the project that we’re going to be talking about today is one that we started in 2023. It involved five partners in East Boston and that includes the organizations the center for Cooperative development and solidarity, CCDs, City Life/Vida Urbana, Maverick Landing, Community Services and Mutual Aid Eastie, as well as Neighbors United for a Better East Boston or New Bay. And these are the covers of our English and Spanish language reports that came out from this that we released last May. And this photo has a number of the folks involved, including people sitting up here.

0:08:25.5 Penn Loh: All right, I’m not going to read all these, other than to say we brought these five partners together to really learn from the experiences that they had with each other through the pandemic and the efforts that are continuing to this day and wanting to learn how have the roles and relationships changed, how has this affected how the groups are doing their. Their work, from community organizing, right, to other types of work that they were already doing in the community. And they were asking the question, what’s next? How can we build on this? And another thing that we found was really important was that there hadn’t been a whole lot of time for folks to do reflection. People were just in it for a while, and there was a lot of exhaustion and burnout. And when we brought people back together, they realized that there were a lot of stories that they wanted to make sure were documented of some of the very hard, but also very beautiful things that had happened over the previous years. So how did we do this work? So there was a team of us from Tufts, UEP, and we worked with the five organizations.

0:09:31.2 Penn Loh: We had three two hour convenings from the spring of 2023 into the fall of 2023, and also over the summer of 2023, we were able to conduct 20 interviews with different folks who are part of this work. Some of them involved in the five partner organizations, and then a number of them who were just involved in many different ways and not necessarily directly with one of the organizations. So it was a chance to really get a number of voices in the mix. So. So let me do a quick, very quick round of intros, but the first thing I want to do is give them, all of our guests, a chance to. To say a little bit more about themselves. But you know what? I forgot even to introduce myself. My name is Penn Loh, and I’ve been teaching here at UEP for a while. And let me let Paulina introduce herself too.

0:10:19.0 Paulina Casasola Mena: Yeah, hi, Rita. Hi, everybody. Thank you so much for joining us. My name is Paulina Casasola Mena. I use she/ella pronouns. And I am a second year in the master’s program at UEP.

0:10:31.6 Penn Loh: Great. And so we have three guests here who are with three of the different organizations who are part of this project. Let me start by just saying your names. And then we will give you a chance to introduce yourselves more fully. Gabby Cartagena, who is with City Life/Vida Urbana now and has done a lot of other things, but we’re really glad you’re with us and thank you for coming. Zaida Adame is with Mutual Aid Eastie. And Zaida, we’re really excited that you’re here as well.

0:11:02.5 Zaida Adame: Thank you for having us. And thank you for the empathy and love you have for communities and for allowing Mutual Aid in our East Boston community to tell our story, to bring it out so other people know what a beautiful neighborhood we have, full of culture and people, strong people that want to move on and thrive this community. Thank you so much.

0:11:27.1 Penn Loh: Then finally, oh, Rita, you are a really large presence in our room now. But, but Rita Lara, who’s the with Maverick Landing Community Services. So, Rita, welcome, welcome. And we’re really glad you could join us. And we know how busy all of you are. So this is really special that we can get your time today. So we’re going to do a round of about four or five questions for our guests, really, so that they can tell their own stories about what some of this work was like. And then we’ll have some time for questions. Pauline and I will also do a little bit of sharing of some of the main findings from the report. But our first question to you all, and just make sure that I’m actually asking what I told you I would ask you, is we’d like you to introduce yourself and the organization you’re with and how you’re connected to East Boston.

0:12:17.2 Gabriela Cartagena: Hi, everyone. Thanks for making it out today. My name is Gabriela Cartegena. You can call me Gabby. I’m Salvadoran, Honduran, Bostonian, meaning that I was born and raised here in Boston, particularly in East Boston. I’ve been there my whole life. I still live there. I work there. And East Boston was the first neighborhood my parents arrived when they refuged out of El Salvador after the US Sponsored workfare in El Salvador. And they actually use collective support, Mutual Aid to come to the United States. And I work full time right now as one of the communications co directors at City Life/Vida Urbana. City Life/Vida Urbana is a housing justice nonprofit that started in 1973, meaning that the organization is now 50 years old. It started in Jamaica Plain and now works in the greater Boston area and particularly supports working people in resisting evictions, foreclosures and rent increases. Using public support, I’m sorry, using public pressure and legal defense to collectively bargain for the best offer for their housing defense against an eviction. And it could be as using collective bargaining power to push back their core eviction date. So just fighting for more time.

0:13:43.4 Gabriela Cartagena: And it could be to as far as agitating and annoying the landlord so much to the point to where the landlord is losing so much money fighting their eviction to evict the person to a point to where we get the landlord so agitated, to the point to where they want to sell the building to one of the partnering social housing partners that we work with as a method, as a tactic, as part of this larger strategy to move more housing out of the private speculative market and into some form of social ownership for permanent affordability and for community ownership. So that’s what I do for work right now. And that’s a little bit about my story and I’m happy to be here. Thanks for having us.

0:14:30.1 Zaida Adame: So I’m Zaida Adame. I was born in Puerto Rico, grew up in the South End, spent a lot of time in New York and my children New York, 25 years in New York and decided to come back home under other circumstances. But I found east Boston as the place I can connect with as the same neighborhood. We were in Manhattan. My kids thought they moved to the suburbs, but it’s not the suburbs, it’s new East Boston. And I did experience, even though I’m from Puerto Rico, I did experience a lot of racism simply because I spoke Spanish. And I just became solidarity with this beautiful community where I connected with share my resources. And I’m not sure that I’m going to be there for the rest of my life. And I want to fight to make it better for my grandkids to grow up in a good, healthy community. So I became involved with Mutual Aid in the middle of the pandemic. I was bored at home. I would walk the street and see people wandering, talk to them. And I found people with a lot of issues, a lot of evictions, mental health, domestic violence. And I would walk them to the park at the library in Rehm park.

0:15:37.4 Zaida Adame: And that’s where Mutual Aid was meeting because we wanted to be open here just every day. We bring someone and they see who were the founders of Mutual Aid and just became and share resources. I just fell in love with Mutual Aid and what they’re about. They in solidarity with neighbors and they share vision, aligned with their vision. Our neighbors come with a vision and hopes and dreams for the country and we connect with that when they arrive here.

0:16:06.7 Rita Lata: My name is Rita Lata And I work at Maverick Landing Community Services. I’ve been in the social services sector and organizing sectors for most of my life. I’m an alum from Tufts. My parents came in ’69 and I grew up in Lawrence, which is majority sales, majority Latino immigrant community. And so I come to East Boston by way of Lawrence and I fell in love with the idea of I transplanted to Boston and doing my social services work here and fell in love with the neighborhood. And that’s what brought me to East Boston because it reminded me in some ways of the neighborhood I grew up in. And Maverick Landing Community Services is we live inside a mixed income housing development in East Boston. So I grew up in public housing and I work in public housing and I champion affordable housing. And I consider the work we do very deeply housing based, which is very personal because it’s where people live. And what we do is we in the heart of the housing development, we support health, promote leadership both for youth and adults through creativity and through health. And so we really provide a lot of kind of wraparound support.

0:17:29.7 Rita Lata: We probably one of the only outside of probably the Mutual Aid office walk in centers where anyone can come in and we say, hello, how are you? How can we help you? And there aren’t a lot of places where you can just walk in if you need support. So that’s really important. I consider what we do really special in the sense that since the pandemic we’ve really expanded our footprint. So we support the housing development, but we also support the neighborhood. And about one third of the people we see are from Maverick landing and about 2/3 are from East Boston. And I also think it’s really special because we like to do it with our. We do our service work with our movement partners and we try. And I do firmly believe that those are two sides of a coin, that movement, that service should be working with movement doesn’t always happen that way. One is more fundable than the other. It’s created the world we see today. And I do that work with that in mind. Thinking about who are we in this space? How do we work within the context of the larger ecology? And as an organization, we’ve supported Mutual Aid both during pandemic and even more recently with a Mutual Aid response to support migrant families at the airport with food when we learned that they weren’t actually provided with dinner.

0:18:54.0 Rita Lata: So that’s who we are. And I’m looking forward to the conversation.

0:18:57.2 Penn Loh: Rita, we’re going to come right back at you with the next question. We’d love to have you share a little bit more about just how some of the early days of the pandemic went. And how you got hooked in through the different, like, how did some of the things that now you’re calling Mutual Aid Eastie. How did you first encounter them and get involved?

0:19:21.0 Rita Lata: Yeah, my first encounter with the Mutual Aid was by way of a friend who was a founder of Neighbors United for a Better East Boston. And she also was no stranger to the work of Maverick Landing. She had come out of a history of really working with Maverick Landing residents. I knew. I partly knew her from that work, and I knew of her work. And she was my first point of entry. She was conducting the orientations and identifying captains, and she said it’d be great if you were a captain for Maverick Landing since you’re already based in the housing development. And so that was our point of entry into Mutual Aid and work. And it was fairly new to me. But I immediately saw the need for a more fluid structure that could embrace both individuals and organizations, especially in emergency response work or in work that results from social disruption because of circumstance, whether it be environmental or social. So that was my introduction. And I think a lot of individuals and organizations were very much working mutually in those days. I think the best organizations just dropped everything and said, what do we need to do? How do we respond? And that’s what we did.

0:20:48.3 Rita Lata: We had never even been a food provider. We just pivoted. And when we couldn’t access food in a pandemic, yes, that infuriated me. We could not access food in a pandemic. Oh, we cleared the path to that food. And it was all underground purveyors of food. Folks that are still around today that aren’t supported by mainstream structures, I should point out, and that we still support and work with, and when there is need, they are there. And I think that sort of distinguishes the folks who are really going to be there to take care of community, the folks who drop everything and respond.

0:21:29.0 Penn Loh: Thanks, Rita. Yeah, I was really taken with just how there was already a layer of folks who were networked with each other, who knew each other. Not all their organizations worked with each other in the way that eventually became. But people were like, how do we figure this out? And. And, Gabby, I want to come to you because I know you were part of a lot of those early days, too, where things were very fluid. And I know you’ve talked about just, like a gazillion WhatsApp chats that were going around to try to for people to try to organize different types of things. But do you want to also share how. What was that initial period like for you and how did you get involved?

0:22:07.0 Gabriela Cartagena: Yeah. This is very odd to say, but I was in the first calls that formed what is now known as EC Mutual Aid. And the reason I say it’s odd to say that is because I do want to recognize the decades of Mutual Aid that has always existed in black, indigenous, immigrant and people of color communities, except that now we formalize it into a nonprofit here in East Boston particularly. And I was the first group of people that challenged what was a person to person grassroots charity managed through a Google form that later transformed very soon and within a week transformed what became and what became a community ran collective response team that was grounded in the realities of desperation and trauma because the government did not react and provide the resources as fast as community needed. And the resources they did provide excluded undocumented communities, which is a large community, undocumented people are a significant part of the East Boston community. And just in, just across the nation, right? We’re talking about over 11 million people who contribute to this country. And it’s really funny because I started those calls through a paid capacity from my previous employer called Green Roots.

0:23:42.2 Gabriela Cartagena: And what people don’t realize is that nonprofits are made by their workers. A lot of the good work that is done in nonprofits is usually done through the initiative of that worker. And there was a point within my employment in Green Roots where I had absolutely no work plan because the pandemic, the state of emergency happened. And I was like, you know what? Let me use this privilege of paid capacity to put in the work to support the formation of what is rapid response work that is not only rooted in, is responding to the desperation and crisis in the community, but also deeply rooted in collective community care. And one of the guiding principles that I worked off of in the moment was a principle that I learned in the organizing with Movimiento Cozecho Movement, a national immigrant rights movement led by undocumented people for dignity, respect and permanent protection of all. And that principle is everything you need can be found in community. So I use that principle to like, to lead what my work plan would be under Green Roots. And I decided before the state of emergency, I’m going to apply for this job opening at City Life/Vida Urbana.

0:24:57.9 Gabriela Cartagena: And I got hired and through the work and umbrella of City Life/Vida Urbana, our executive director of the Moment, Lisa Owens, ask the organization like, hey, who here as paid organizers is going to step up and support these Mutual Aid efforts in the city? Not just thinking about East Boston, but also thinking about the strong Mutual Aid happening in Dorchester as well. And I was one of those folks that stepped up and the work under City Life, their guiding principles when it comes to community work is.

0:25:36.2 Gabriela Cartagena: And in regards to eviction defense and just in general is connecting this trifecta of what is community work. We’re talking about service, right? Which in city life looks like the providing of free legal services weekly for limited consultations. We’re talking about advocacy, right? Advocacy that doesn’t protect people from eviction immediately, but works towards decades, has a legacy of decades of organizing to lift the ban on rent control again, right? We’re talking about. And the advocacy, decades of advocacy and organizing that led Massachusetts to the place to where we had the strongest eviction moratorium in the entire country of the United States that not only protected renters, but also protected homeowners who were unable to pay their monthly mortgage payments.

0:26:27.4 Gabriela Cartagena: And I’m also talking about that third trifecta, that third element, right? We’re talking about service advocacy, but also organized because organizing is what challenges the status quo and structural issues that not only perpetuates evictions, but perpetuates this dominate cultural hegemony of if you’re facing eviction, it’s your fault, which is horrible. And we’re working at City Life/Vida Urbana. My approach to Mutual Aid shifted dramatically because under that leadership, I was reoriented in what these different branches of community work could look like and is made up of. And how this mesh, this blend of this trifecta is able to provide the strongest way of providing community work, not just siloing service, advocacy versus organizing, how do we blend it all together and do it together. But also being really strict. I was really. The whole organization had a wake up call on City Life’s decision to approach Mutual Aid networks in East Boston and Dorchester as a way to expand its resources to community members that can be passed through these different Mutual Aid efforts. There was tension within the organization around why aren’t we doing a food pantry at the City Life office? Why we got to feed the people.

0:27:53.3 Gabriela Cartagena: And it’s yes, people need to be fed, but City Life’s role is to support people in the eviction defense. Especially at a point where hundreds of thousands of people lost their jobs and did not know that there was an eviction moratorium that was very much like a big learning curve around the rigidness and sometimes you could call it even as discipline militancy as to what are the organizational expectations of this movement organization expecting of you for the sake of bringing forth the mission and vision in relationship with Mutual Aid. We knew that city life had to be a part of Mutual Aid efforts as a way to provide this expertise, for lack of a better term around eviction defense. But there was a lot of learning curves in how we worked because the heartbeat of City Life/Vida Urbana anti eviction defense organizing relied on the in person weekly meetings that happen in Jamaica Plain and Wisconsin simultaneously. And those meetings had to pivot to digital only. So we had to, I had a lot all the different organizers. We had a lot of sessions with community members one on one in parks or outside the steps of their front porches teaching them all right, this is how you download Zoom.

0:29:16.6 Gabriela Cartagena: This is what Zoom is. This is how do you log into the Zoom. And City life even had a particular donor drive where we funded and looked for funds to specifically sponsor and finance technological connection WI-Fi providing WI-Fi and cell phone and or iPads to identify to identified key member leaders to allow them and create a path for them to continue organizing.

0:29:45.1 Gabriela Cartagena: Because there was already a lots of decades, years of worth of investment in people’s leadership development to allow them to plug into these different Mutual Aid efforts in the way that made more sense to them as a way to contribute to the movement, but also to make sure that city life’s role has always been like being like a movement incubator in a way in these past 50 years. And part of that incubation was making sure that our member leaders had the digital literacy, learned digital literacy and had the digital tools to continue organizing across Boston.

0:30:24.4 Penn Loh: Thanks, Gabby. You’re raising I think a lot of the issues that we spent a lot of time trying to understand of the complexities and challenges. Like what you were saying about these different ways that groups have been doing their work and you mentioned non profits. I think a lot of us in the room have critiques of nonprofits and nonprofit industrial complex. Right. But just so interesting to see how those things were mixed up and Zaida you got involved in Mutual Aid Eastie, which I think is still trying to figure out. Like I don’t think it is exactly a nonprofit, but it’s anyway you can… Why don’t you share a little bit more about Mutual Aid Eastie, how you got involved.

0:31:02.8 Zaida Adame: During the pandemic. We know there were problems before the problem pandemic came and it made it worse and pandemic went away and the problems were still there. So we needed City Life/Vida Urbana, who specialized in their own skills, decided to create Mutual Aid to leave something in place to deal with this issue in the community. And I remember we were giving food out, but food with dignity and respect. We have families cooking at home for the neighbors because we didn’t just want to throw boxes of canned food, processed food at their doors. We wanted them to get a meal that was given with love and dignity. We even found a mosque in one of our Muslim neighbors who worked for us for a while, who borrowed the kitchen at the mosque and cooked thousands of meals for Muslims in that community.

0:31:54.4 Zaida Adame: Mutual Aid always believed that volunteer is from the heart. And Leo, I know he doesn’t want to be called a leader, but he led us into that thinking and we were all volunteers. I want to acknowledge, Eddie Claudia, Dr. Nina Estrella, who’s our leader and our supportive and who believes in the dream community and supports us a great deal with Grant Valinda, who was amazing.

0:32:26.7 Zaida Adame: And we became volunteers non pay providers in the community. And we were doing it from the heart. And Leon Daisy, who started Mutual Aid decided that we needed to get paid. That’s why we started asking for grants, but from people that share the vision. We have declined grants from people who don’t share the vision of community and just want to give to promote themselves and their corporation. So we accept. We do fundraising and sometimes share our profits with other organizations. With Cosecha who now were able to acquire driving licenses for 17 years Massachusetts for people to be able to drive, go out of the city, buy cheaper food, take their families out, things that they were not able to do. We’ve partnered with Cosecha to work on rent control to make sure that our residents remain in the neighborhoods they don’t have to go out. And every time a family leaves, it breaks our hearts and a new family comes in and we never get to connect with them. So Mutual Aid has been a big part of supporting community. We accompany people to court when they have an eviction. We send them to city life and they need a company.

0:33:41.4 Zaida Adame: We go to court, we go help women get restraining orders. We reach our people at the health center. We have created a space for our neighbors to come and feel at home. We build the trust, give them the space. We have a group that meets on Saturdays. It’s called Manualidades, where all the women come and get together and crochet, make art things that they’re doing in the country they have not had the opportunity to do. We have a healing get together once a month where people come and express their pain if they had a lost one. And they connect through healing. We have a training, we got a grant to teach English, and we went the other route. We said, there’s people that want to learn Spanish. So we created a space and connected people who wanted to learn Spanish with people that wanted to learn English. And it was, I think, 17 weeks and people came out of there speaking the language they wanted to speak. We also are on our second round of empowering women who can work to become babysitters. And we have helped them get their license, do all the stuff that you need to do to be a legal babysitter or a nanny.

0:34:56.5 Zaida Adame: And that’s empowering them. We have. We’re teaching them how to do resumes. We’re teaching them how to. We started from having an email doing Zoom. Thank you to Rita Lara, who gave us his support in getting them laptops and giving us her space to educate these women who now can connect with people back home through Zoom. And it’s like, amazing. Oh, my God, there you are. And it’s not always now a phone call. This is what Mutual Aid is in solidarity with neighbors. We have open hours on Thursdays and Fridays. We call it Hola de cafecitos. We have community people who want to get involved and volunteer and neighbors who come to chat. We’ve had neighbors who ran into each other who didn’t know they lived down the street when they came here. And so in Fridays, we have. We try to have people who have nobody to come and speak about what they do when people come and listen. And we empower people to give back to us. We expect them and we teach them to give back to your neighbors. So if I go with someone to question court and somebody else needs a company, we call that neighbor that I went to court, who now knows how to accompany someone.

0:36:09.3 Zaida Adame: So it’s a community. And our vision is that one day that this beautiful community will not need government assistance. They can survive on their own, either by farming or exchanging or babysitting for each other, driving each other and so on.

0:36:26.6 Penn Loh: I’m going to go to you first because I think our next question is about sharing a moment from particularly the pandemic period. And I know there are so many, but I guess I’m just asking you to pick and tell the story of one that you’d like to share with folks.

0:36:44.2 Zaida Adame: Yeah, I barely remember a moment that one neighbor called me one night, late at night, her relative was in the hospital. They called her that she was going to pass away and she couldn’t be there to say goodbye. And she said, will you drive me to Brigham and Women’s Hospital? And I said, what’s going on? Are you okay? She said, no, he’s going to be gone in a few minutes. I know what room he is and I want to see him. And I remember her kneeling and looking at the window and somehow saying goodbye to him. And broke my heart. And that stuck to me. And it was a horrible moment because I couldn’t do much for her, but just drove her there. But also remember that’s all she needed. And that’s I gave that and she will always remember that. And to me that was very compelling.

0:37:38.0 Penn Loh: Thanks for sharing. That Zaida, I think it’s just, I think anytime we start to reflect on this period, there was a lot of very difficult moments. And just being with people like I think we all remember that point where that wasn’t very possible. And to be able to provide that was very special. And that’s something that you focused on. Thanks for sharing that. Gabby, why don’t, why don’t we go to you.

0:38:04.8 Gabriela Cartagena: I reflected on two moments, but I’ll focus on an actual moment. But just to give some context, it’s not the greatest moment. It’s really sad. And one of the hardest moments that I experienced as a sealed organizer doing anti eviction work during the pandemic was calling back people from the City Life/Vida Urbana housing hotline from the Spanish calling list. By the time I inherited it there we were behind like a hundred calls with my colleague Francis Amador, who is now directing the north side organizing work right now. And I specifically remember this one man that I reached out to. I’m forgetting his name, but I remember his face clearly. It was this senior elder gentleman, Guatemalan from East Boston. He lived in Eagle Hill. And I met him through the City Life housing hotline. And he was facing an informal eviction in the sense that the their primary tenant so in his apartment was renting him a room and he was being evicted from his room. And he called the housing hotline because he was facing this informal eviction. So I let him know about the eviction moratorium. I did all the these other resources lists.

0:39:35.8 Gabriela Cartagena: I connected him to EC Mutual Aid. He was able to get food delivery bags and he was even able to get a small redistribution check that was primarily merit managed by nube and I remember around maybe like a few, a month or two after, a few months after meeting him, getting a call from one of my friends. Her name is Glory Bell her name is Gloria Rivas, fellow Salvadorian who is the legislative staff manager with the representative AJ Madara from East Boston. She called me and she was like hey Gabby, since you work at City Life I wanted to call you and let you know that I met this elder Central American man around Maverick Station and he’s homeless, trying to see how we can get him support. And at that moment was when I realized that one of the elders that I was supported was informally evicted, meaning that he did not go through the court proceedings. He was many of the probably hundreds of thousands of undocumented people that feared going to eviction housing court and allowed, I wouldn’t say a lot of themselves, but was pushed by fear and was displaced.

0:41:04.5 Gabriela Cartagena: And I remember feeling guilty and like blaming myself for him being homeless, saying oh, I could have done more like I should have done more, I should have done X, I should have done Z. But processing that with other movement lawyers and even certain organizing leaders within city life, I had to really understand honor the limits of what it means to be a community organizer. And a lot of this work, a lot of organizing work really depends on the individual’s empowerment for self advocacy and the ability for growing. Someone’s individual empowerment really relies on in person relational development in organizing terms we call relational organizing, which depends deeply on being able to be person to person and talk to each other. And that was missing in the organizing we did during the pandemic because we were so limited in how we approach the organizing work for the sake of our own public health safety and moments like that just really test your self care and like historic trauma recovery because it’s just really hard. And a lot of the work that City Life does, a lot of the anti eviction work isn’t about we’re going to defend your home for you.

0:42:45.9 Gabriela Cartagena: It’s about we are going to provide you the organizing tools and basic eviction defense education for you to be better equipped to fight for your home. And defend your home. So I would say that experiencing those limitations in the organizing work we were doing during the pandemic was and hearing about people you’re directly supporting being and becoming homeless. It’s probably one of the hardest realities that I witness and experience and learned from like at least in the early days of the pandemic.

0:43:31.8 Penn Loh: Thanks Gabby for sharing that Rita we’re going to turn to you and ask the same thing, if you would share a moment.

0:43:41.2 Rita Lata: The moment I’m going to share is one that I was just reminded of when you shared in your opening, when you shared the… There was a picture where me and my husband were in the picture and we were carrying a box. And our organization, Maverick Landing Community Services, beyond really all kinds of food, housing and supportive services. We also have programs for youth and families, and we have a kids makerspace and we have a teen makerspace. Just before the pandemic, my makerspace coordinator had gotten just boxes and boxes and rolls of materials donated, like fabric. And when the pandemic hit, I heard a call from one of our partner organizations in this work. Luz Zambrano from the center for Cooperative Development Solidarity caught on a call that she needed fabric. So I said, we can do this. We have all kinds of fabric. And my husband and I grabbed the boxes and we brought them over to her.

0:44:48.7 Rita Lata: And they were working with a cooperative called Puntada who was sewing masks for people. And that was beginning. When I tell you that the path that in some ways is a creative movement and resilient movement, that is.

0:45:05.1 Rita Lata: That was a pandemic and I think is part of Mutual Aid work in any kind of response work. And that’s it. That’s a sort of. In some ways, it’s a branch that opens into another branch that opens into another branch which you would have never taken had you not stepped on that first branch. And that was a branch that opened into a current collaboration where youth, where our young people in our teen maker space make these journals in collaboration with Puntada. So they laser cut the local materials we purchase and they bring them to the co-op. And people from the co-op sew the covers and then the young people retrieve them. And then we laser cut whatever people want onto logos and names and we personalize them. And to this day, the Mutual Aid is still a very active customer and supporter of that work. And there’s been a lot of solidarity in supporting the young people. All the proceeds they get to use, how they want to take trips and do things with. But it was this beautiful locally made product that we finally brought the prototype, the final prototype, 2020. And we couldn’t have done that without the cooperative.

0:46:30.9 Rita Lata: You needed that. The co-op was an important piece of the puzzle. We had tried and tried to bring that to get it finalized, and we just couldn’t because we needed Puntada. So that’s the story. I’ll share this it’s guess it’s the story of resilience.

0:46:45.3 Penn Loh: Thanks so much, Rita. I know I had two other questions I said was, but I’m just going to ask the next one for right now. Yeah. So what I’d like to ask all of our panelists now is what’s an important lesson that you or your organization learned from going through this period of the pandemic and the emerging Mutual Aid practices and networks. So I don’t know if anybody feels excited to go first to respond to that. Zaida. Okay, go ahead. Go for it.

0:47:15.3 Zaida Adame: So I learned how strong my community is and how resilient they are and how stronger they became after the pandemic. I learned from them so much. I got strength. I learned so much from my team. Like I said before, Eddie, Leo, Herzberg, Claudia Belinda, how we became stronger with each other, how we supported and care for each other at the same time, caring for the community. And I learned about organizations in East Boston that are not greedy. Like Channel Fish is one of the organizations that gives so much to our community. They given us space because you said nonprofit or not, most of the stuff are donated. People donate our coffee, our sugar, our milk. And Channel Fish has given us a space where they provide paper, ink, everything. They don’t charge us any money. They cook for us in the kitchen, and they give space to other organization who we share the space with. So I learned about people giving back who have so much and give back to the community. And I go back to saying that I learned how strong these people who come on a journey to look for a dream, who escape violence.

0:48:31.8 Zaida Adame: And I wanted one lady I remember from Colombia, she said to me, you came here and you encountered. She said, no, we have this virus in Colombia. So she said she came from Colombia and it wasn’t the virus, but guns and getting shot and getting kidnapped. And this virus she thought was they were protected. It wasn’t as bad, but so they come already traumatized. And I learned that we can survive this and survive more if we stay together as a community and we work as team with other organizations to share the same vision. Love my team. Thank you. They inspire me. They give me hope and strength.

0:49:13.7 Penn Loh: Go for it, Rita.

0:49:15.0 Rita Lata: Yeah. Can you just repeat the question so I’m grounded in it?

0:49:18.9 Penn Loh: Yeah. What’s a lesson learned from the pandemic? Mutual Aid experiences that you’d like to share?

0:49:26.6 Rita Lata: Oh, so many lessons learned, but I think the most important one is that this work cannot happen. Right. We can’t do the work of really nurturing people and community in a silo. It must be done in partnerships. That’s probably the most important lesson. And I would add to that it does need to be a values grounded. These we have to have alignment in terms of how we relate to people and to the world. I think that’s really important. I would say that’s very central and that’s what’s really kept us. I would say even still organized and however loosely at times because things are ever changing. But also really we all have ongoing content actually interaction. Now that I think about the people who are part of the Mutual Aid and CCDS and New Bay, I consider friends and colleagues and in the work who will always, in some ways the work is far less lonely. I feel like you will always have people who have your back and that is a win and that’s probably write the good stuff that’s come out of all the disruption.

0:50:50.3 Penn Loh: All right, thanks Rita. All right, Gabby, this is the last round.

0:50:55.1 Gabriela Cartagena: I would say one of the biggest lessons I learned in this work. Obviously I want to reiterate what Zaida and Rita said around at least for me, being reminded of the resilience and collective people power not just within East Boston, but across Massachusetts. There was a statewide network of Mutual Aid work being done across the state. And also the importance of intersectionality and cross collaboration across different sectors of the movement, service work and advocacy. But I also learned this term, I will quote one of my colleagues, Andres Del Castillo, that this work is hard work and it’s what we call heart work. Like the impact that we support in communities and in empowering people in reclaiming their story is beautiful. And then reclaiming the story to the point to where they’re no longer blaming themselves for facing an eviction. They’re connecting their story to the failures of the government in protecting them from staying in their homes. And one of the biggest lessons I learned during the pandemic particularly was that the housing crisis doesn’t exist because the system doesn’t work. It exists because that’s the way the system works. And I’m directly quoting Peter Marcuse, which is a quote that we stand by at City life because if the government wanted to, we could have lifted the ban on rent control decades ago if the government wanted to, they could have banned no fault evictions if they wanted to.

0:52:47.7 Gabriela Cartagena: But unfortunately we live in a state where power is consolidated in the State House, in a place in which the majority of state representatives are politicians, are not renters. They’re homeowners. A big part of them are landlords. Check out the Boston Globe investigative article that investigates those. Ask yourself why don’t we have certain governmental protections in Massachusetts and Boston? Right? Why are we passing symbolic legislation on the city level that’s passing rent stabilization at a 10% cap when people’s wages are barely even increasing 5% a year? So one of my biggest lessons was how deeply ingrained is the systemic changes we need to see happen are and how us in this community work within service, advocacy and organizing. How it’s so important for us to get to a place where we are shifting the conditions we are living in to get to a place to where it’s easier to do the service work, where it’s easier to do the advocacy by organizing, where it’s easier to and more affordable to buy your groceries weekly and a place in where you can actually afford and have a right to decent health care, dignified health care where you actually have the right to for a plate of food, a right to housing, a right to live without fear of displacement or deportation.

0:54:26.8 Gabriela Cartagena: Those are some of the biggest lessons I learned during the pandemic.

0:54:32.3 Penn Loh: Thanks, Gabby, and thanks to our three panelists. We are going to take just a few minutes to share some of the findings from our report and then we’ll open it up for we’ll hopefully have about 10 minutes left for questions and we’ll do a closeout. Turn it over to Paulina and I’m going to ask also Paulina to just say, very short, about how she got involved in this project and she’s been the student who’s been longest involved.

0:54:57.4 Paulina Casasola Mena: Thank you for sharing so much. I started at UEP in the fall last year, but I really joined the project in at the end of May and I knew I wanted to do research during my time at Tufts, but I knew I wanted to participate participating community action research and really continue to do some sort of organizing and be connected to movement folks, not just go inside a classroom and not think about the world. So this project was an opportunity to do that and also collaborate with an amazing team and develop new relationships with people in East Boston. I really feel like every time that we went and did an interview, it wasn’t just like data, it was a treasure that I knew people were trusting me with. It was an opportunity for me to do work in Spanish after eight years of only doing work in English. It was an opportunity for me to go back to a lot of my roots and I feel like it was one thing to read Dean Spade Mutual Aid book. And another thing to remember the times that people had given me and my grandma rides to to the hospital and had share food or different items during special moments where we really needed help from others.

0:56:20.0 Paulina Casasola Mena: And it was also and it sparked an opportunity for me to be in community with folks in East Boston and just continue supporting their work. And I’m really glad that we’re able to have you all here to tell your stories and to document the work that people did in the pandemic in order to help residents in East Boston survive. People that just were not being acknowledged by the system that they helped sustain. So we have a lot of wonderful findings, and we really encourage you all to read the report. But some of the most salient findings include that this work emerged out of existing initiatives, existing relationships, years of organizing that people have been engaged in, and it foster new collaborations, new opportunities for trusted relationships with social service agencies, with funders, with different organizations across East Boston. And it looked all kinds of ways. There were people that were on call to help others arrange funerals. There were people helping get food at the table. People who were initially on the line to receive groceries because they couldn’t access food stamps were then the ones that led food distribution efforts months later and continue to do that today.

0:57:45.1 Paulina Casasola Mena: There was also emotional support, this sense of acompanamiento, which is very present in Latino culture, just like being with one another, as well as helping people. Understand that they have something to contribute and that they are valued and needed in their community. We have some definitions of Mutual Aid. Daisy, who was one of the initial founders of Mutual Aid Eastie, said to us that to her, Mutual Aid is a different way of saying reciprocity. It’s a movement. It’s a way of life. And Dr. Nina also mentioned that Mutual Aid is bringing people together and fostering community care. And we also heard that Mutual Aid was an engine that kept the community going. So another critical thing that happened during the epidemic was this sort of mindset shift from scarcity, which is very present in nonprofits and our current world, to abundance, recognizing what resources could be redistributed and how solidarity could boost community care, as well as trying to find ways in which people could address the gaps that were present in government systems like stimulus checks or food stamps, and help sustain one another. And at the core of all of this, work with deep relationships and trust.

0:59:19.8 Paulina Casasola Mena: So, yeah, so part of this changing mindset is also acknowledging that people don’t want to go back to a system that doesn’t work for them doesn’t work for us, but rather build, quote Dr. Nina Build a new world while the other, while the old world still exists. And understanding what the resources are, whether it’s like social capital, deep relationships that can help these kind of like the building blocks of this new world because things have changed.

0:59:55.5 Penn Loh: So we did have some findings that were about what people aspired to for the future of Mutual Aid. And I’m not going to read all this just because I think I’d like to actually give an opportunity for Zaida and Gabby and Rita to actually say a little bit more about because that was our final question was what do you see as the future of this work? Right. And I think there are some aspirations. Not everybody thinks this, but a lot of folks are like, hey, we saw some new things happening in Mutual Aid that emerged that had always been there, but came out in a different way, maybe more visible and maybe gives us hope that we don’t have to stick to the old system. And I think that what you were saying, like that system definitely is working to keep people in the conditions that they are. Right. So if we’re going to change that, maybe Mutual Aid can be part of a different system moving forward. I am going to just. I’ll just show this for a sec because I’ll just say Luz Zambrano from CCDS was someone who was pretty involved in this work and helping to support that co op that Rita was talking about.

1:00:54.9 Penn Loh: But she was saying, I’ve been fighting the system for 34 years, thinks it’s time to create our own, of which I think Mutual Aid is a part of that. So again, we’ll share all these slides as well. But I’m going to stop sharing this so that we can give our panelists a chance to really share their final thoughts on what do you see as the future of this work we will.

1:01:17.0 Zaida Adame: Continue to make empower people. I’m hopeful that people will have a place to live, a healthy place, that they will have health insurance, that their children can grow up getting an education, that they can continue to build community and just bring more people together, make people feel like they belong and not welcome them. That welcome thing. If you belong in this community, help them settle and make our community stronger with the vision that one day they will not need government, that they can survive on their own. With Lucia Bruno making cooperative with Canaan building more city farms and people can grow their own food. We can make our own toothpaste. We don’t have to buy from corporations. And that’s what Mutual Aid hopes for to bring more people together, to bring more organizations to work together.

1:02:10.5 Penn Loh: Yeah, and Zaida. I just wanted to say, I think something that I learned a lot from hearing you all talk about the future is just how you’re trying to not be like a non-profit and to say what Mutual Aid Eastie is, is this network where these values and this care actually happens. So I just wanted to appreciate that.

1:02:28.2 Zaida Adame: We’re not an organization. We’re not accountable. We don’t have bosses. We depend on each other. We support each other and we work with donations. Our neighbors, who can donate a dollar a month, will bring us coffee and will bring us lunch or babysit for our neighbor that needs child care or pick up somebody’s child. We continue to be strong as a whole with organizations like that. We can make our community stronger with their powers and skills and talents. And I like to end with the quote that Audre Lorde said, Community cannot be a community without liberation. And I love that quote.

1:03:09.9 Penn Loh: Thanks for sharing that.

1:03:11.5 Paulina Casasola Mena: Gabby, do you want to go next?

1:03:13.4 Gabriela Cartagena: So my hopes for the future of Mutual Aid, I misspoke in the beginning, I was like, yeah, Mutual Aid is a nonprofit. They have a fiscal sponsor. They’re technically not a nonprofit. My bad. I misspoke there. But my hopes for the future of Mutual Aid, which honestly is what I’m seeing right now, I like to say the present is the future because what you do now creates the future. Remember that when you create your daily habits. But I remember when we were having these research conversations, I was thinking about, all right, what are the ways in which Mutual Aid can benefit this movement for deepening and broadening social justice, housing justice, economic justice, xyz so many justices, and I still believe this, and I said this to many people in Mutual Aid that I see Mutual Aid, it’s superpower East Boston Mutual Aid superpower being their ability for doing relational organizing. And because of that relational organizing, having the superpower of mass turnout for either advocacy events, advocacy initiatives, advocacy campaigns, events. There is a project right now in East Boston that is living under Maverick Landing, called the East Boston Spatial Justice Lab.

1:04:41.1 Gabriela Cartagena: And through certain cultural artistic events we’ve done to increase the sense of belonging, we’ve leaned on EC Mutual Aid to support that initiative through that mass turnout superpower that they’ve been able to do because of that deep relational organizing that’s being done in Mutual Aid. And also this power of creating alternatives, Zaida that mentioned the manualidades workshop, that is a way for women to come together and use their hands and express themselves, to create and express themselves Right. To build a sense of belonging and to break away from the individual silos. Because even within East Boston, there’s so many people that they visually know each other. Like, I can identify your face, but I don’t really know you. And part of that superpower of honing into the alternatives is also the digital literacy workshops that Zaida mentioned, which was done in partnership with, with Maverick Landing, where they have sessions where months long session to teach people. This is how you create an email. This is how you send emails. This is how you access Microsoft Word.

1:06:05.6 Zaida Adame: Medical record.

1:06:06.6 Gabriela Cartagena: Medical records. And there are spaces like that in the city, but they’re not in. They’re. They’re just in English, right. And/Or there’s this like years long wait list to be able to get that access. So my hopes for Mutual Aid is to continue leaning into this superpower of mass turnout and the ability to create alternatives, which, if y’all are interested, we’ll bring it into organizing terms. These are forms of theories of change when it comes to social movement work, right? The theory of change, of creating alternative spaces, the theory of change, of relational organizing, the theory of change of mass turnout. These are important characteristics in movement building work that either organizations which can be nonprofits lean on, or social movements that don’t have a nonprofit status also lean into. Because these are theories of how we can approach the work. But what really matters is what are we doing in practice? What are we doing in practice? And sometimes you can do practice and not know the theory because you practice it so much. Or people get so caught up in practice and pedagogy that they forget to apply those ideologies, pedagogies, into practice, into practice, to be able to make it part of your life.

1:07:47.0 Gabriela Cartagena: So those are my hopes of the future, future within Mutual Aid. And honestly what I’m currently seeing. So I’m very hopeful.

1:07:56.8 Penn Loh: Thanks for that, Gabby. All right, Rita.

1:08:01.5 Rita Lata: I see the future of Mutual Aid and its strength also like Gabby and a relational network. I see the future is in growing that network. I also see Mutual Aid. What I’ve learned over the years, it happens everywhere, all the time. We don’t always call it Mutual Aid. It’s a spontaneous sort of human response, right. In a lot of ways. And I think we need to really name it, elevate it, make it right. Important sort of value in our society, right. Like this idea that, yeah, we help people, we support people, we give them tools, we empower them, we. And it’s not all about structuring it in an organization. Organizations. I learned the limitations of organizations, too, in this work, and I think this is where we really need networks. I think networks and individuals and organizations should be all working together. That’s not always the case. I think there’s still a strong siloed mindset as we return back to the old. We see it creeping into the world. And I think it’s our responsibility to continue to support a more fluid, more generative ecology. And I’m proud to say, and I want to elevate Gabby in the work that she’s done with us as a sort of artist in residence with the East Boston Spatial Justice Lab, which lives within Maverick Land and Community Services and really works with all of the partners that we worked with through the pandemic, CCDs, New Bay Mutual Aid Eastie, and also we’ve also worked with the Transformational Prison Project and City Life/Vida Urbana.

1:09:53.7 Rita Lata: So really, all of us and others like working together to continue to create spaces that really consider how intersectional all of our work is and how we need to continue to work together to create a more generative ecology and how we’re more than just ourselves and just our organizations. We’re much larger. And if we stay together and keep working together, that’s how we really like, I think, make things better for everyone.

1:10:27.8 Penn Loh: Thanks so much. Rita. Rita I understand that you may also need to step off at some point. So before you do that or might need to do that, let’s actually just give a round of applause for our panel.

[applause]

1:10:40.1 Penn Loh: I want to say we are all. And I continue to be inspired by just hearing the work that continues to this day. And I am hopeful that we can see more of this in more places. And I know some folks have already gone because we’re at our closing time, but for folks who is it okay if we maybe take just a few questions for.

1:11:03.5 Paulina Casasola Mena: Yeah, okay.

1:11:05.2 Penn Loh: Maybe we. If there are any folks who want to put questions in the chat and maybe I’ll ask Bella to maybe identify some and. But there’s people in here in the room, too. Thanks. And I just want to repeat the question so it gets on the zoom recording Johnny was talking about. Organizing in your own community can be very difficult, and especially that was the case in the pandemic. But were there some beautiful moments as well?

1:11:29.1 Zaida Adame: To me was when we opened up our office and I was able to hug my neighbors. That was. I’m a hugger. Hugger. I’m from New York and I used to hug. And when I hugged the first neighbor that came in. She says, you’re acting like you never seen me for years. And I said, but… Just hugging people, that was to me and feeling that support and love for me, my community, and my neighbors.

1:11:54.2 Paulina Casasola Mena: You want to go, Rita?

1:11:55.7 Rita Lata: I feel like when I shared my moment, I shared my good moment. That’s probably my tendency. Don’t look at the dramatic stuff, but, oh, goodness. I think a feel good moment for us was really restarting our after school kids maker space. I think to see the kids back in the space was just like… And because it was hard, that program was shuttered in for two years. And you have to appreciate the kind of after school program we have. Our coordinator lives in Maverick Landing. She’s also the icy lady. She sells icy from her window. We’re very community based. To have her come in and be and lead in that space when we opened was, I think, very precious.

1:12:42.4 Gabriela Cartagena: Yeah, I would say, and I know Rita said this at some point, but I created some or deepen some really amazing friendships that came out of this work. Some of these people are in the room right now, so shout out to you all. And also just the amount of community resilience that I took part in and in growing that and then strengthening that is definitely one of the most beautiful takeaways, not just during the pandemic, but just generally in community organizing work. That’s why we do it, for strengthening the supporting the strengthening of empowerment of communities and collectives across the city. And maybe just to highlight a particular moment, there was a photo of this food pantry that was in Eagle Hill. And that’s when I learned from one of our neighbors, Dominic, who was telling me, he was like, yeah, we bought all this stuff from Home Depot because we create. I’m not a Restaurant Depot because we created this pay $5 share. And that’s how we were to buy everything. And I was like. Like, y’all created a subscription. Like, that’s on WhatsApp. That’s crazy. And I remember going in there with my camera.

1:14:12.6 Gabriela Cartagena: I’m also a photographer, and I remember going in there with my camera and taking photos and asking this one community member, I was like, hey, can you, like, stand there? Hold your box up because you have the gloves, you have the face mask. She had the face shield. She was like, suited up. And I’m just like, chilling with, like, my scrappy fabric mask. And I was like, can I take a photo of you? And I take a photo of her. I take a little portrait and then she’s wait are you Gabby from City Life? Like it is Gabriela and I’m like yeah she’s yo so Alejandra and she was like one of the long term member leaders of City Life/Vida Urbana and I was like oh my God I like talking to you so much and didn’t know even I knew what you look like from photo but I just couldn’t recognize you because you’re like suited up right now.

1:14:57.9 Gabriela Cartagena: So I remember just hugging her and just her being so happy because she’s so charismatic and super expressive and and yeah and it’s just really beautiful to reflect on that moment and also reflect on certain women who in the times of the pandemic like they were in domestic violence relationships and post eviction moratorium post the urgency of the height of COVID those women are no longer in those relationships and yeah that I would say that transformation and them making those decisions in their lives because of the community work, the community support, accompaniment solidarity that they experience experience allowed them to leave a relationship that was not serving them.

1:15:56.9 Penn Loh: I think we are going to formally draw this to a close. Just want to thank again all the folks here. I didn’t say before, but Natasha is part of our UEP students who are helping to put this event on and brought all the snacks. So thank you for doing that. Thanks to Bella for running the Zoom. I know this was not the easiest Zoom situation to handle and thank you again Gabby, Zaida and Rita. You’re all amazing people.

1:16:27.8 Zaida Adame: Thank you for accommodating me on the zoom.

1:16:29.4 Penn Loh: I’ll keep in-touch with you all. We’re so glad you could be with us and for all the folks who joined us today, thank you for coming.

1:16:38.1 Tom Llewellyn: We hope you enjoyed this week’s presentation. Click the link in the Show Notes to access the video, transcript and graphic recording or to register for an upcoming lecture. Cities@Tufts is produced by the Department of Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning at Tufts University and Shareable. With support from the Barr foundation, shareable donors and listeners like you. Lectures are moderated by Professor Julian Agyeman and organized in partnership with Research assistants Amelia Morton and Grant Perry. Light Without Dark by Cultivate Beat, our theme song and the graph recording was created by Anke Dregnat. Paige Kelly is our co producer, audio editor and Communications manager. Additional operations, funding, marketing and outreach support are provided by Alison Huff, Bobby Jones, and Candice Spivey, and the series is co produced and presented by me, Tom Llewellyn. Please hit subscribe, Leave a rating or review wherever you get your podcasts and share with others so this knowledge will reach people outside of our collective bubbles. That’s it for this week’s show.

This article originally appeared on Shareable.net.

Read the full article at the original website

References:

- https://pennloh-practical.vision/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Mutual-Aid-East-Boston-Final-Report-May-2024-English.pdf

- https://www.jessmilner.com/

- https://www.shareable.net/mutual-aid-101/

- https://www.shareable.net/cities_tufts/mutual-aid-lessons-from-east-boston/

- https://bsky.app/intent/compose?text=Mutual%20Aid%3A%20Lessons%20from%20East%20Boston+https%3A%2F%2Fwww.resilience.org%2Fstories%2F2025-03-04%2Fmutual-aid-lessons-from-east-boston%2F

- https://x.com/intent/tweet?text=Mutual%20Aid%3A%20Lessons%20from%20East%20Boston&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.resilience.org%2Fstories%2F2025-03-04%2Fmutual-aid-lessons-from-east-boston%2F

- https://www.linkedin.com/shareArticle?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.resilience.org%2Fstories%2F2025-03-04%2Fmutual-aid-lessons-from-east-boston%2F&title=Mutual%20Aid%3A%20Lessons%20from%20East%20Boston&summary=Last%20fall%2C%20Tufts%20University%20Distinguished%20Senior%20Lecturer%20of%20Urban%20Environmental%20Policy%20and%20Planning%2C%20Penn%20Loh%2C%20hosted%20a%20discussion%20following%20the%20release%20of%20a%20new%20report%2C%20Mutual%20Aid%20lessons%20from%20the%20COVID%2019%20pandemic%20strengthening%20civic%20Infrastructure%20in%20East%20Boston%20through%20Community%20Care.&mini=true